NOTE: This post contains spoilers for the HBO TV series Game of Thrones, as well as George R.R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire novels.

--

Hello, everyone! Long time no blog! #31DaysIBPOC brought me back -- thanks, Dr. Kim Parker & Tricia Ebarvia, for the invitation!

My last post was on March 31, 2016. Life has been a whirlwind since then. Last year, I made tenure at Penn, and was promoted to Associate Professor of Education.

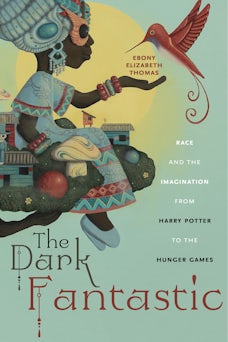

My book, The Dark Fantastic: Race and the Imagination from Harry Potter to The Hunger Games, will be officially released from NYU Press next Tuesday (May 21!). The seeds of my book can be found in my earliest posts here, "The Imagination Gap" and "Why Is Rue a Little Black Girl?"

My graduate students and I still maintain our booklists over on @HealingFictions, and we hope to (finally) launch our website later this year.

And the most popular show on television, Game of Thrones, took a sudden nosedive this spring. It's on track to finish tomorrow with one of the most controversial finale episodes in recent memory.

There are many people who are currently debating the ultimate fate of one of the protagonists, Daenerys Targaryen, a dragonriding exiled queen from the deposed ruling family. I'm among them.

But this post is not about Daenerys.

This post is about Missandei.

*

I said:

Now will the poets sing,-

Their cries go thundering

Like blood and tears

Into the nation’s ears,

Like lightning dart

Into the nation’s heart.

*

The HBO television series Game of Thrones is based on a series of novels by fantasy author George R.R. Martin, collectively titled A Song of Ice and Fire.

In the novels, Missandei of Naath is a ten-year-old girl from the Summer Isles. She is described as having "a flat face, dusky skin, and eyes like molten gold." She and her brothers were captured by slave traders when she was a young child. Her brothers were pressed into service with the Unsullied, a famed enslaved army, noted for being castrated in their youth.

While racial and ethnic characteristics in Martin's stories do not always coincide with our own (after all, Dany in the books has "purple eyes"), the show's casting of mixed-race British actress Nathalie Emmanuel seems to indicate that Missandei on the show can be read as a character of color in our world.

Specifically, a Black character.

*

In the YA literary world, there has been much talk recently about whether race in fantasy is analogous to race in the real world, and if so, what to do when books feature racist characterizations, worldbuilding, plots, themes or settings.

I'm not here to rehash those conversations. Yet.

I am here to pay my respects to Missandei.

*

Remembering their sharp and pretty

Tunes for Sacco and Vanzetti,

I said:

Here too’s a cause divinely spun

For those whose eyes are on the sun,

Here in epitome

Is all disgrace

And epic wrong,

Like wine to brace

The minstrel heart, and blare it to song...

*

Four observations follow. Perhaps more, after the show and the academic year are (blessedly) done, and I have more time.

But for now, I offer just these four.

1. In other people's fantasies, we are rarely allowed to be children. The decision to cast an adult is an example of Black girl adultification, something that scholar Stephanie Toliver has noted in her recent work on Rue in the The Hunger Games. That takes nothing away from Nathalie Emmanuel's incredible performance. After all, Judy Garland's young Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz was restoried into Stephanie Mills' young adult Dorothy in The Wiz on Broadway, and eventually transformed into Diana Ross' grown-up Dorothy in the musical film of the same name.

Adaptation is an act of interpretation. The fact that showrunners David Benioff and Dan Weiss read about little Missandei, then chose to double her age changes the character from the novels. While other characters have changed, Missandei's literal adultification is notable.

What was it about little Missandei on the page that made Benioff and Weiss choose to make her an adult on the screen, instead of a little Black girl? Was it to provide Dany with a (Black) best friend? Why, then, did the screenwriters not evolve the story accordingly?

2. In other people's fantasies, we are rarely allowed to exist for ourselves. We exist only to be of service to others. Missandei was the "Black best friend" chararacter -- sort of. When we meet her in the novels and on the show, she is the enslaved translator for Kraznys, one of the Good Masters of Astapor. Dany uses her dragons to sack the city, then frees Missandei. Missandei chooses to remain with Dany as her handmaiden, translator and confidante.

There were many other narrative choices that could have been made by the writers.

They could have had Dany offer Missandei unconditional freedom.

They could have had Missandei return to Naath for a time -- opening space in the narrative for her to exist for herself, on her own terms -- and showing us another culture before her story rejoined Dany's.

There are a thousand other possibilities. The problem is the imagination gap. Writers can't imagine that characters like Missandei might have plausible motivations beyond service, obedience, and knowing one's place.

Although Missandei's age changed from A Song of Ice and Fire to Game of Thrones, her storyline did not evolve accordingly. In the books, she is emerging as a strategic mastermind (yes, at 10 or 11 years old! I know!). On the show, little of that complexity is apparent.

Although Missandei is free, her story remains tied to Daenerys'.

She is the Black best friend...

Sort of.

3. In other people's fantasies, we are assumed to be sexual objects. We are also seen as incapable of the full range of human emotions, including love. The last glimpse we've had of Missandei in the books is when she aided Ser Barristan in taking control of the court of Meereen after Daenerys flew off on her dragon.

On the show, Missandei, as an adultified Black girl character, was sexualized. Of course.

Sexual stereotypes about Black girls, women, and femmes abound in our culture. I will not rehash them here. But the nature of the comments about Missandei and her Unsullied lover, Grey Worm, displayed peculiar anxieties around sex, race, love, and desire.

Martin's books were noted for being explicit long before they were adapted for the small screen, and Game of Thrones became notable for its use of "sexposition." But on a show that seemed to enjoy making even the most libertine viewers wince, Missandei and Grey Worm were one of its healthiest couples.

That didn't stop fans from joking about Grey Worm's genitalia, though.

As with many such characters, the range of human emotion afforded to Missandei and Grey Worm is limited. They love Daenerys because she freed them from enslavement. They are clearly in love with each other. However, we don't see Missandei cultivate any other close friendships. Grey Worm's bond with his Unsullied brothers is meant to be assumed, but he is their general, and is giving them orders.

Missandei's and Grey Worm's origin stories -- enslaved as young children -- mean that they do not have access to love from their families and communities. Although it can be argued that being part of Dany's retinue could be consider an alternate sort of family, that's not quite the same thing on a show where one's House -- quite literally, genetically related family -- means everything.

We do not hear either character express much desire to go home to Naath and the Summer Isles until Season 8. This desire was sparked by the racist treatment they experience at the hands of the Northern subjects of House Stark (the region and House we the viewers are supposed to be rooting for, mind),

It is yet unclear whether Game of Thrones understands that this, too, is tragedy.

4. We always die in other people's fantasies. (Other people seem to fantasize about Black death. Endlessly. Often needlessly.)

In the end, Missandei died.

(The Black girl always dies.)

Here's what I wrote about that in The Dark Fantastic...

In her introduction to her masterpiece, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, Christina Sharpe asks:

Sort of.

3. In other people's fantasies, we are assumed to be sexual objects. We are also seen as incapable of the full range of human emotions, including love. The last glimpse we've had of Missandei in the books is when she aided Ser Barristan in taking control of the court of Meereen after Daenerys flew off on her dragon.

On the show, Missandei, as an adultified Black girl character, was sexualized. Of course.

Sexual stereotypes about Black girls, women, and femmes abound in our culture. I will not rehash them here. But the nature of the comments about Missandei and her Unsullied lover, Grey Worm, displayed peculiar anxieties around sex, race, love, and desire.

Martin's books were noted for being explicit long before they were adapted for the small screen, and Game of Thrones became notable for its use of "sexposition." But on a show that seemed to enjoy making even the most libertine viewers wince, Missandei and Grey Worm were one of its healthiest couples.

That didn't stop fans from joking about Grey Worm's genitalia, though.

As with many such characters, the range of human emotion afforded to Missandei and Grey Worm is limited. They love Daenerys because she freed them from enslavement. They are clearly in love with each other. However, we don't see Missandei cultivate any other close friendships. Grey Worm's bond with his Unsullied brothers is meant to be assumed, but he is their general, and is giving them orders.

Missandei's and Grey Worm's origin stories -- enslaved as young children -- mean that they do not have access to love from their families and communities. Although it can be argued that being part of Dany's retinue could be consider an alternate sort of family, that's not quite the same thing on a show where one's House -- quite literally, genetically related family -- means everything.

We do not hear either character express much desire to go home to Naath and the Summer Isles until Season 8. This desire was sparked by the racist treatment they experience at the hands of the Northern subjects of House Stark (the region and House we the viewers are supposed to be rooting for, mind),

It is yet unclear whether Game of Thrones understands that this, too, is tragedy.

4. We always die in other people's fantasies. (Other people seem to fantasize about Black death. Endlessly. Often needlessly.)

In the end, Missandei died.

(The Black girl always dies.)

Here's what I wrote about that in The Dark Fantastic...

In her introduction to her masterpiece, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, Christina Sharpe asks:

What does it mean to defend the dead? To tend to the Black dead and dying, to tend to the Black person, to Black people, always living in the push toward our death...

It means work. It is work: hard emotional, physical, and intellectual work that demands vigilant attendance to the needs of the dying, to each their way, and also to the needs of the living.

This question is not limited to humans who have been labeled as Black in the past and present, both quick and dead, but extends to Black characters, and to the very idea of Blackness itself. As the title of Sharpe’s book suggests, this is an ontological question that every Black child, woman, and man is confronted with throughout the course of a lifetime. It is a question that demands an answer.

The wake, according to Sharpe, is the path behind a ship, keeping watch with the dead, coming to consciousness, all at once. Throughout The Dark Fantastic, we have witnessed Black girl characters caught in the wake within the storied realms of the collective imagination...

I am by no means the only one who has observed the myriad ways that the fantastic, the speculative, and the collective imagination have rendered Black presence impossible and Black nonexistence compulsory. Most Black fans and other fans of color have thought quite a bit about our precarious state even within realms of supposedly infinite possibilities.

During a Twitter chat, an observer by the handle @relicUA noted that “I think poor nonwhite people are in a state of quantum super-position, such that they only exist when the narrative requires.” Indeed, young Black women and girls exist in a state of quantum superposition in the fantastic. They cannot exist, and yet, they must: when it comes to the fantastic, Schrödinger's cat is a young Black girl...

(Schrödinger's cat is Missandei.)

In the wake of these shadows and echoes, it seems vital to examine the ways that Black writers, fans, and audiences are narrating the self into existence in the face of erasure—indeed, have always had to read ourselves into fantastic canons that excluded us. The traditional fantastic has historically assumed a White audience, and, in turn, those endarkened and Othered have had to read those stories to understand the cartographies of the imagination. In contrast to histories of fandom and audience that portray audiences for the speculative and the fantastic as predominantly White, new work from scholars like Rebecca Wanzo and André Carrington sheds light on the ways that Black fans and audiences have always interpreted fantastic media that does not always imagine us as part of the audience—a view that I share.

It is my hope that future scholars and researchers will extend Sharpe’s call for wake work into the dark fantastic.

(Missandei, like us, lives in the wake.)

*

Surely, I said,

Now will the poets sing.

But they have raised no cry.

I wonder why.

--Countee Cullen, "Scottsboro, Too, Is Worth Its Song," 1934.

*

(Let others sing dirges for their fair dragon queen!

Missandei, too, is worth her song.)

(2019.)

This blog post is part of the #31DaysIBPOC Blog Challenge, a month-long movement to feature the voices of Indigenous and teachers of color as writers and scholars.

Please CLICK HERE to read yesterday’s blog post by Dr. Debbie Reese titled “The I in #31DaysIBPOC is for Indigenous.” (and be sure to check out the link at the end of each post to catch upon the rest of the blog circle).

You can read all of the blog posts this month here.